A new type of pattern for aggregating bicycle frames allows for more adaptability.

Continue reading

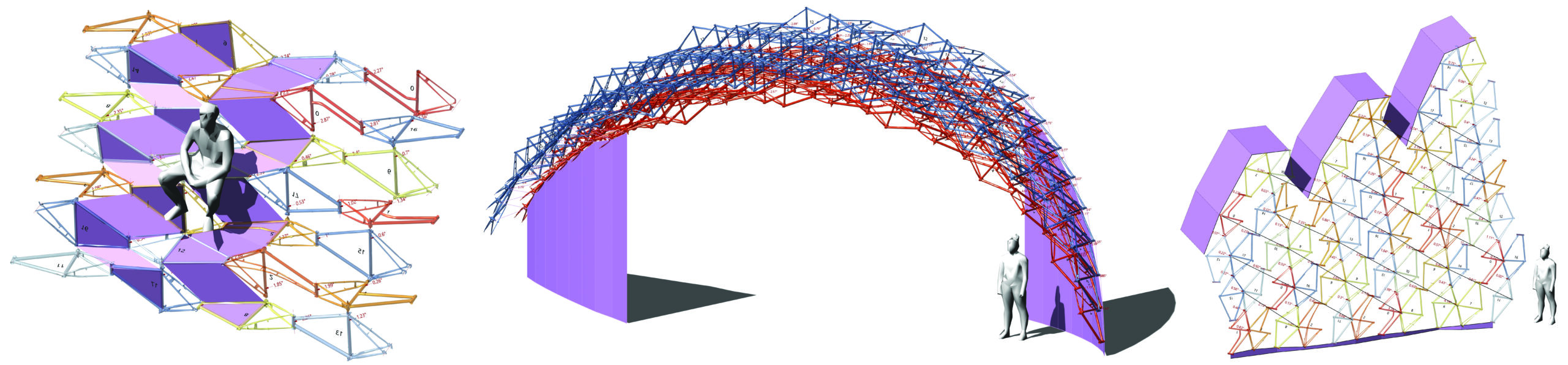

Based on the specific potentials, we sketched potential use case scenarios for three different patterns.

Continue reading

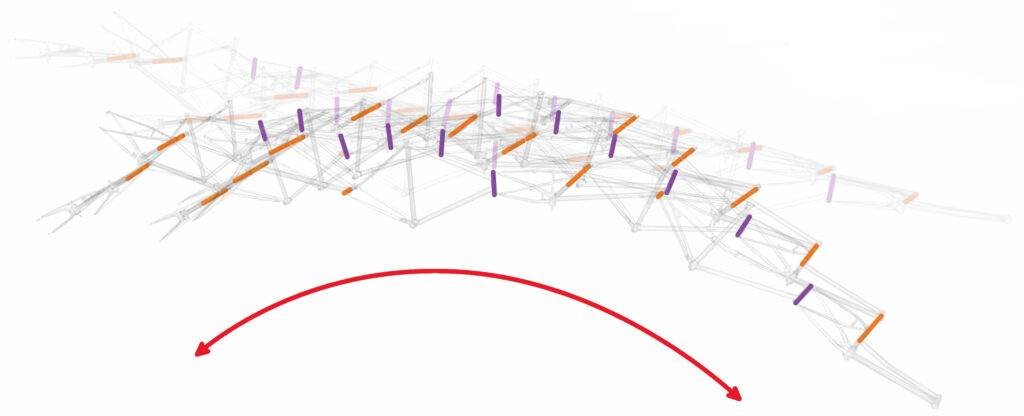

Besides varying capabilities for adapting to form variation of constituent parts, the surface-based bike-frame aggregations we studied previously, also have different bending flexibility.

Continue reading

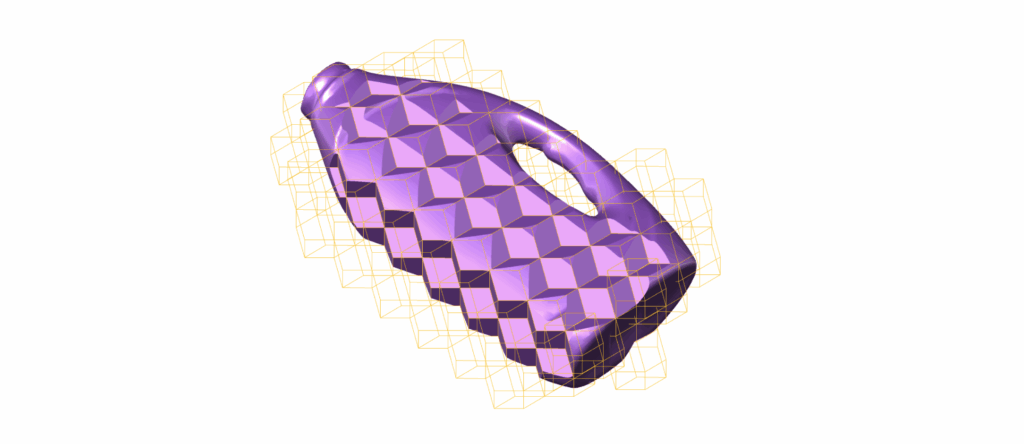

In this part of our ongoing exploration into how detergent bottles can become building blocks, we return to the idea of designing the shape of the bottle. Not by changing the form in complex ways, but by applying what we’ve learned from space-filling geometry.

Instead of completely transforming the bottle, we focused on minimal modifications, while making it suitable for a second life as a modular element.

Learning from the WOBO bottle – (you can read more in our previous blog post) – we were fascinated by how the design embedded reuse directly into the form of the packaging.

We’ve been exploring the idea of giving packaging not just a second life through recycling, but a second function through design. This led us to experiment with how detergent bottles could be transformed into interlocking, modular components, inspired by Japanese joinery, 3D puzzle logic.

We’re returning to the detergent bottle — and to the techniques we explored earlier with pressed plastic panels in the Pearse structure. But this time, the goal is to preserve more of the bottle’s original shape while still transforming it into a structural element.

Continue reading

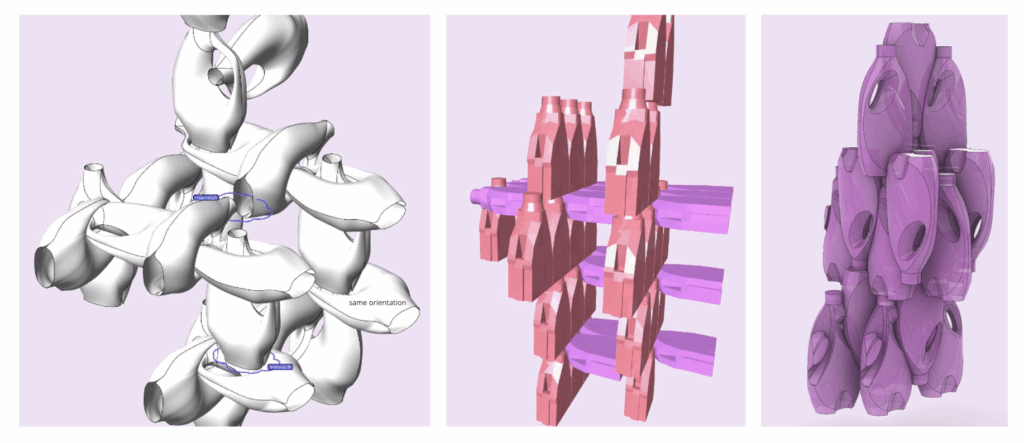

In this phase of the project, we’ve shifted our perspective. Until now, the physical experiments revolved around pressing artefacts into a predefined geometric mold. Specifically, we worked with the Peter Pearce’s Curved Space System, using saddle pentagons to form a continuous surface. This approach treated geometry as the fixed system, and artefacts as materials to be adapted. But what if we turned the concept around?

Continue readingIn an effort to advance discrete element aggregation using the Grasshopper3D plugin WASP (and Andrea building new features into it along the way), we are exploring a ‘sequence-based design’ approach and identified Peter Pearce’s Curved Space Diamond Structure as an ideal foundation.

Applying a clustering algorithm to an inventory of irregular unique objects can help to reduce the complexity involved in designing with such parts significantly. By dividing the inventory items into groups with similar characteristics, each group can then be represented by one “proto-part” instead, therefore reducing the amount of unique elements to be handled in setting up aggregation logics and the aggregation processes.

The decision about the number of different groups (Fig. 1) can be completely left to an algorithm (depending on various predefined – by the programmer – conditions) or be manually determined by the user/designer.